My name is Dylan Voorhees and I am the Clean Energy Director for the Natural Resources Council of Maine (NRCM). NRCM played an active role in advancing the Maine Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) policy passed in 2007 with strong bipartisan support. And we were one of many diverse parties to work on developing the bill before you today. There are many reasons to support this bill, from environmental and public health benefits to job creation and economic development. I would like to focus on one important reason: This is a balanced energy policy that is consistent with the region’s necessary and beneficial transition toward a more diverse, reliable and cleaner electricity mix. While this transition will not complete over the medium-term framework in this bill, the next decade represents a pivotal stage for resource diversification.

The transition toward a renewables-based grid is already under way. It is one that is driven by the collective efforts of the New England states, not by any one state alone. Unlike previous periods, over the past several years Maine has relied on (or allowed) other states to take the lead. The time has come for Maine to help lead again, especially because our renewable-resource rich state has disproportionately more to gain from development of new renewable capacity.

The policy is “balanced” because it reflects some common ground across diverse stakeholders who have different goals and do not agree on everything. It is also balanced from an energy resource perspective because it sets a reasonable pace for change and it balances the use of new and existing resources.

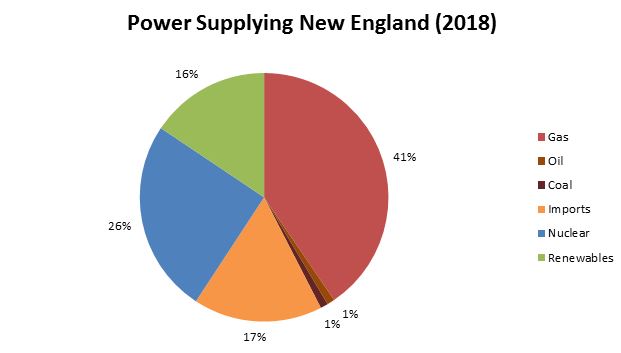

As you can see in the following chart, in 2018, New England got 41% of its electricity from natural gas power plants (red), which of course must import their fuel. In-region renewables made up 16% of supply (green), with the rest from nuclear (blue) and electricity imports (orange), with less than 2% from coal and oil. Less than 45% of our electricity (green and blue) comes from indigenous resources that do not rely on some kind of imports.

Our high dependence on natural gas makes us especially insecure. Sometimes gas prices are low and supply is adequate. But occasionally neither is true. The region has struggled with the idea of investing relatively massive amounts in new natural gas pipeline capacity to meet the needs during those few expensive hours. Some of the reluctance to do so comes from the price tag, but it is magnified by the knowledge that we must reduce our dependence on natural gas over the coming decade, for climate and other reasons. The question comes down to: What kind of future are we investing in? We say focus primarily on a local, renewable future.

The need to replace power plants that will be retiring over the coming years gets a lot of attention in energy circles. However it is easy to lose track of the forest for the trees. New England will continue to have very large amounts of fossil-fired capacity for a long time to come. Yes, there are costs to keep some of these plants available to operate some of the time—but those costs pale in comparison to keeping those plants available and having them operate many more hours to provide large volumes of our electricity. The most secure, stable, and affordable future is to generate the largest portion possible of our total electricity need from renewables like wind, solar, and hydro, while filling in the gaps with other solutions (gas, storage, demand response).

A Maine policy requiring 80% renewables by 2030 must be considered in the regional context. A combination of LD 1494 and existing policies in other New England states would put us on track to get 30% of the region’s power from in-region renewables. This will be excellent progress, with major benefits for Maine. However, the change should not be exaggerated, including by those focused on capacity and resource availability. Our supply mix and the availability of capacity to meet demand during key hours are very different, with different markets and policy responses. The need for gap-filling resources will increase gradually, especially as renewables in the system approach 50%, 60% and 70% of our mix.[1]

In the “reference case” (i.e. no new policy) used by consultants examining this proposal, wind and solar increase significantly and use of natural gas decreases to around 24% of our regional mix by 2030. If Maine adopts LD 1494, natural gas is modeled to shrink to closer to 22% of our mix. These reductions are incredibly valuable for our economy, our environment, our energy security and independence; even a small additional decrease can have enormous benefits. However, you should be clear that natural gas is not going away soon. (Neither is nuclear, which is expected to provide close to 20% through 2030.)

NRCM strongly supports the commitment by Governor Mills and others to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions by 80% by 2050 (and 45% by 2030, which is also in line with a regional commitment that Governor LePage joined). To do so will require an integrated, economy-wide strategy with significant emphasis on electrification. A steadily increasing portion of our power coming from renewables is a very important part of that strategy. I’m happy to answer your questions on that point.

Maine’s current Class I RPS did not have the impact that many of us hoped for. It did not play a major role in driving investment in new renewables. That is because the market signal was too weak, and because it contained a wide provision allowing existing renewables to qualify as new.

LD 1494 addresses those experiences and makes improvements in several ways. Although it is a small matter, the bill narrows the provision for additional “refurbishments” to qualify as “new.” (Honestly it is not clear that any additional refurbishment qualifications are needed.) Secondly, the bill takes a more integrated approach to “new” and “existing” renewables. Under this policy, Class I will consist primarily of brand new renewables, especially over time. But the inclusion of current refurbishments and a small amount of existing hydro resources gives some balance to the class. This is an example of compromise in the policy before you.[2]

Third, the bill includes very important provisions for long-term contracts as a compliment to the RPS. Others will hopefully speak to these provisions, however you should know that NRCM strongly supports the contracting language and views it as critical to increasing renewable development and maximizing environmental and ratepayer benefits.

We urge you to adopt this legislation and set Maine on a course for a cleaner, more diverse, and more independent energy future. Thank you.

[1] As we go forward, the idea of “baseload” power will become less and less relevant. Our “base” will be increasingly made up of renewables, which while intermittent on an individual facility basis are less so on a system wide basis. When we maximize their utilization, these renewables provide the lowest cost power. The gaps will be filled with flexible resources. Capacity resources that can fill the gaps or meet peak needs are NOT the same as baseload power. Investing in a lot of additional traditional baseload (fuel-based or nuclear) only erodes the economic advantage of renewables that we want to use whenever they are available, and does not meet the gradually increasing need for flexible, gap-filling resources.

[2] Looking within Maine, if you pass LD 1494, it is reasonable to expect that by 2030 35% of our supply would come from traditional, existing resources, 10% from “refurbished”, and 35% from brand new resources.