More than a decade ago local, state, and federal officials, including then–U.S. Department of the Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt, joined staff, board, and members of the Natural Resources Council of Maine and hundreds of other Mainers on the banks of the Kennebec River to witness a landmark occasion: removal of the Edwards Dam in Augusta. It was a ten-year effort sparked by NRCM more than a quarter-century ago.

“In 1976, when the Edwards Dam on the Kennebec River in Augusta was breached in a flood, two members of the Natural Resources Council of Maine’s board of directors— Bob Dow, a biologist with the Maine Department of Marine Resources, and Jon Lund, an Augusta lawyer and legislator—led the call for its removal,” recalls attorney Bill Townsend, a long-time NRCM member and widely known champion of river restoration. “That call went unheeded at the time, and the dam was rebuilt. When the dam came up for re-licensing by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) a decade later, that call had not been forgotten.”

The dam’s owner, Bill notes, wanted to preserve the status quo at this lowermost dam on the river, at the head of tide. “The company proposed that the new license not require construction of a fish passage, and that trap-and-truck of river herring continue for the duration of the 30-year licensing cycle,” says Bill. Federal and state fishery agencies and a consortium of non-profit environmental groups thought otherwise. NRCM, joined by Kennebec Valley Trout Unlimited, the Atlantic Salmon Federation, and American Rivers, created the Kennebec Coalition, which cited a number of biological and economic studies predicting that restored sea-run fisheries would far exceed in value the electricity that the dam produced.

The dam’s owner, Bill notes, wanted to preserve the status quo at this lowermost dam on the river, at the head of tide. “The company proposed that the new license not require construction of a fish passage, and that trap-and-truck of river herring continue for the duration of the 30-year licensing cycle,” says Bill. Federal and state fishery agencies and a consortium of non-profit environmental groups thought otherwise. NRCM, joined by Kennebec Valley Trout Unlimited, the Atlantic Salmon Federation, and American Rivers, created the Kennebec Coalition, which cited a number of biological and economic studies predicting that restored sea-run fisheries would far exceed in value the electricity that the dam produced.

A decade of contentious proceedings followed. Then, in 1997, in a historic first-in-the-nation decision, FERC concurred that the ecological value of a free-flowing river was greater than the economic value of a dam. The Edwards Dam was removed on July 1, 1999. “A seventeen-mile flat-water impoundment was transformed overnight into a vibrant river with rapids, riffles, pools, and gravel bars,” says Bill. “The biological results were spectacular—all of the predictions for rapid recovery of sea-run fish were borne out in spades.”

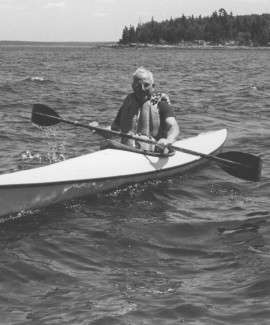

Return of the fish—striped bass, shad, and many others—meant the return of Bald Eagles, Osprey, and other wildlife. The river’s rebirth also rejuvenated communities along the Kennebec; birders, hikers, and picnickers enjoy new trails, riverfront docks, parks, and boat launches that have sprung up, and paddlers and anglers have become a common and colorful site.

NRCM’s work restoring the Kennebec helped lay the groundwork for removal of another dam. For more than 100 years, the 470-foot Fort Halifax Dam in Winslow blocked the mouth of the Sebasticook River, the largest tributary to the Kennebec. The dam’s owner, Florida Power and Light, received permission from the state and federal governments to remove it, but a small group of people living along the slow-moving, lake-like section of river above the dam fought its removal, tying the issue up in the courts through five years of lawsuits. NRCM and other members of the Kennebec Coalition successfully fought these lawsuits, and on July 17, 2008, the breaching began.

Today, more than two million alewives swim from the Atlantic Ocean up the Kennebec every spring in what is perhaps the largest alewife run on the eastern seaboard. “NRCM brought dedication, focus, staff time and volunteer time to the table,” says Bill. “Had it not been for the work of NRCM in coordinating the work of the members of the Kennebec River Coalition, the outcome might have been different.”.