by Douglas Rooks

For 30 years, there’s been no fiercer, more consistent, or passionate advocate of protecting the Maine woods and enhancing its wildness. Cathy Johnson came to the Natural Resources Council of Maine (NRCM) in 1990, and two years later began working full-time on the North Woods project – a role she fulfilled for the past three decades, as Forests & Wildlife Director, until retiring in February.

Cathy at the Katahdin Woods & Waters National Monument. Photo by T.Kilgore/NRCM

Her legacy for NRCM mirrors the values and ideals expressed at its founding more than 60 years ago, and which continue today – using science, law, and the power of everyday people united in a call for change.

Though “wilderness” is not a designation for state public lands programs — Baxter State Park is the unique exception — the value of the 10.5-million-acre Unorganized Territory, almost all forested, is incalculable, in Johnson’s view. “There’s nothing like it anywhere else. It’s still the largest unfragmented temperate forest in the world. It has global significance.”

She was there for all the great battles of the 1990s onward – the “Ban Clearcutting” referendum in 1996 and the competing Forest Compact, attempts by Plum Creek to site massive development around Moosehead Lake, protecting the Allagash Wilderness Waterway, and finally, leading efforts to create the Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument – the capstone of her long advocacy career.

In interviews with Johnson – and eight of her NRCM colleagues, professional allies, and citizen collaborators – the picture emerges of a remarkable journey focused on a single, overarching goal. The promise was there at the beginning, said Brownie Carson – who hired her and worked alongside her for more than 20 years.

“She was a young lawyer in private practice in Damariscotta,” the former NRCM Executive Director recalls, and not at all typical of the time. The two had met in law school, and Carson liked her toughness from the beginning, saying, “She’s a strong and principled person. She made some of the male lawyers in Lincoln County pretty uncomfortable.”

At NRCM, though, she fit right in. “I’ve always believed that the key to success is hiring people smarter than you are, and putting them to work,” Carson said. At a small organization – NRCM had 15 staffers vs. nearly 30 today, “the key factors are the chemistry among people, and the commitment to do the work that’s at the core of the organization.” He never had any doubts about Cathy Johnson’s commitment, or her teamwork.

Pete Didisheim, who joined NRCM in 1996, became Johnson’s boss as Advocacy Director, and never worried about being caught short. “She has her own network of experts and policy advisors,” he said, “pretty much everyone with a deep and abiding interest in the North Woods.”

By the time Lisa Pohlmann became Executive Director, in 2011, Johnson was senior attorney. “Our offices were in opposite corners of the building,” Pohlmann said. She often made the trip because, “I always wanted to check in on whatever campaigns she was involved in.” What impressed her most was, “She does not have a big need to be loved by everyone. She has a great ability to connect with people, but also an amazing ability to compartmentalize. You can be on opposite sides, and it never affects the relationship.”

Others depict a keen legal mind combined with passionate advocacy. as Jeff Pidot, assistant Attorney General for natural resource and conservation issues, discovered. His role defending state policy sometimes put them on opposite sides, but Pidot became friends with Johnson and her partner, Jon Luoma, with joint outdoor excursions. Pidot is awed by her ability to be at home anywhere, “She thinks nothing of disappearing into the Himalayas for weeks.”

It was in the 1990s, a turbulent decade for forest policy, that Sally Stockwell, long-time conservation director at Maine Audubon, began working with Johnson. Stockwell has compiled a long list of Johnson’s accomplishments – broad, as well as deep.

Did she really attend every Land Use Regulation Commission (LURC) meeting? Yes, except when another staffer did. This is no small commitment; the agency, since renamed the Land Use Planning Commission (LUPC), meets all over the state, often for the entire day.

For Karin Tilberg, now director of the Forest Society of Maine in Bangor, it was her work with Johnson through the Northern Forest Alliance that began a fruitful long-term relationship. An outgrowth of the Northern Forest Lands study, the Alliance sought ways to preserve the 26 million acres of forested land across northern New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine, ultimately leading to major conservation deals in the late 1990s.

Cathy speaking at wildlands bill press conference in 1998

Regulating clearcuts was premised on the short rotations preferred by the multinational paper companies that owned the North Woods for generations, but with rapid sales to dozens of new landowners— real estate investment trusts, TIMOs, “kingdom lot” millionaires, and forest liquidators — the focus shifted dramatically.

“All the assumptions we had about good policy changed almost overnight,” Tilberg said.

It was then, said Sally Stockwell, that she realized what an asset Johnson was. “We would always turn to Cathy for the detailed analysis of what was going on. She really dug into things. She knows more about what’s happening in conservation and land management, on the public side and the private side, than anyone else.”

Yet is wasn’t only information being offered, Stockwell said. “She was always there with the initial analysis. It was wonderful to have somewhere to start, but she always opened it up for questions and comments, asking ‘What should our next steps be?’”

Whether the topic was ecological reserves on public lands, establishing backcountry designations for non-motorized recreation, or just finding the ideal canoe route, “Cathy had incredible passion, and compassion, for the North Woods,” Stockwell said. Her intensity at public meetings led some to see her “coming across as a little harsh,” but such impressions were quickly dispelled. “She’s willing to work with anyone, commercial forest landowners included,” Stockwell said. “I don’t know anyone who knows more, or cares more.”

Karin Tilberg said of Johnson, “She was persistent in a way that couldn’t be dismissed.” Even in seemingly hopeless cases, “She kept showing up and people said, ‘Well, she’s here again.’ Some would have been worn down by that. She wasn’t.”

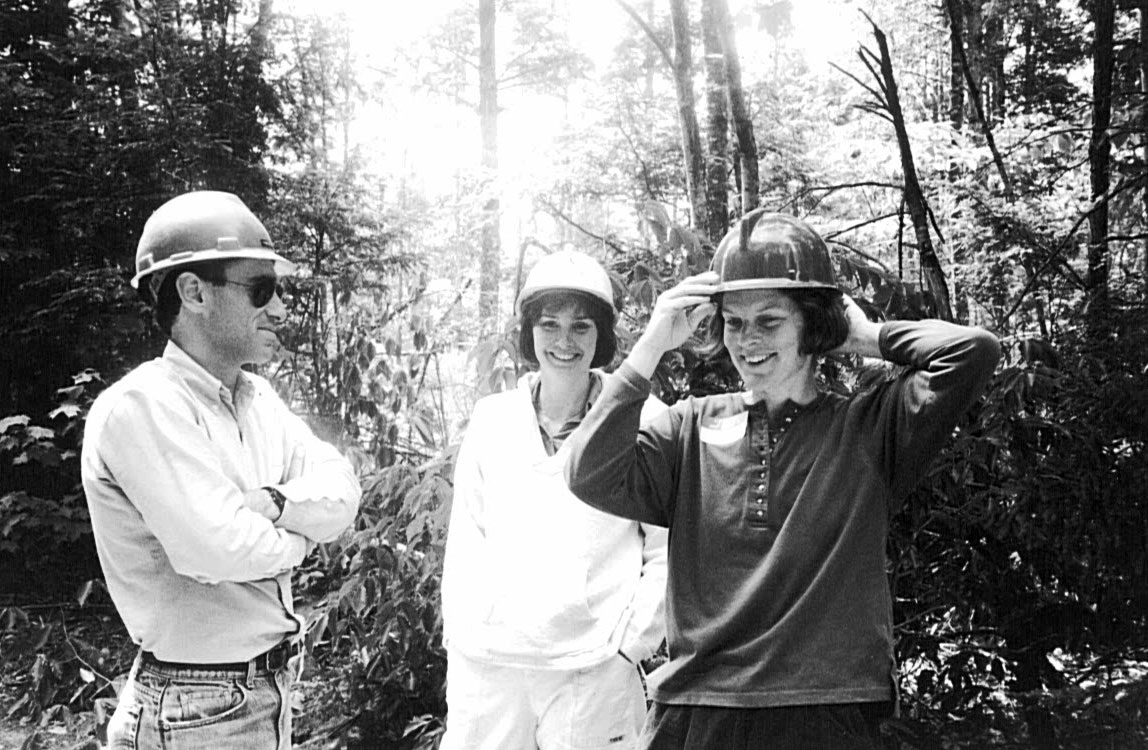

NRCM former staff Ron Kreisman and Jean Key Maginnis with Cathy Johnson on a board & staff trip to Maine’s North Woods

The second decade of Johnson’s work featured one of the biggest development schemes ever unveiled for the North Woods — Plum Creek’s plans, unveiled in 2005, that would have scattered second homes all over the landscape, and led to just the kind of development LURC was supposed to prevent. Had Plum Creek been able to “sprinkle lots all over the woods,” said Pete Didisheim, it would have “opened the door to any and all development.” The years-long battle led to approval of a plan substantially scaled back and focused more on the developed areas along the west shore of Moosehead Lake, but still unacceptable, in Johnson’s eyes.

NRCM took the unusual step of taking a Maine regulatory agency to court in 2009, and won after a Superior Court trial before Chief Justice Thomas Humphrey. Brownie Carson remembers “jubilation” in Johnson’s voice. He was surprised, given the deference usually shown by courts to agency decisions, but the victory didn’t last. Humphrey’s ruling was reversed on appeal by the Supreme Judicial Court in 2012.

Still, Johnson was instrumental in pushing for better terms in the 363,000-acre conservation easement Plum Creek donated, and the company finally abandoned its approved plan earlier this year. “From the point of conservation, it was a great outcome,” Johnson said. Yet, ever vigilant, she worries that recently approved “adjacency” standards from LUPC could lead to unwise development by the new landowners.

This period also featured pitched battles over the Allagash Wilderness Waterway, an area Johnson knows as well as anyone. Sportsmen pushed for increased access at John’s Bridge, and Johnson pushed back. Carson recalls that even he thought perhaps a compromise was in order, but he respects Johnson’s lifelong pursuit of “maximum possible wilderness.”

This photo is from a 2001 trip on the Allagash Wilderness Waterway with Dean Bennett (far left) and others during the fight over John’s Bridge & negotiating the River Driver’s Agreement.

As it happened, Johnson’s most successful effort still lay a decade into the future.

Cathy Johnson has some personal attributes that may seem surprising.

She’s a talented amateur musician. Johnson played viola as a child but took up violin after meeting Jon Luoma – also a violist. They played together in ensembles, and she was a 25-year member of the Colby Symphony Orchestra. She later joined the St. Cecilia Chamber Choir, with concerts throughout Midcoast Maine; she hopes performances resume after the pandemic.

A talent more closely related to wilderness excursions, one Karin Tilberg often observed, is Johnson’s canoeing prowess. Their trips date back to Northern Forest Alliance days and continued when Tilberg was deputy conservation commissioner. She recalls trips on the Allagash, and on the Penobscot East Branch, which flows through the new National Monument.

Cathy paddling on the Allagash Wilderness Waterway

“Cathy is an amazing bow paddler,” Tilberg said. “We tackled tough rapids. She always knew where the holes were, doing quick cross-draws and push offs.” Tilberg sees this as a metaphor, on forest issues, of Johnson’s “willingness to be up front, and be on the front lines, to lead without looking over her shoulder.”

Yet it wasn’t all about white water. Johnson was always interested in the human history of a place, including Bible Point on the Mattawamkeag West Branch, associated with Theodore Roosevelt and now a state historic site. On cross-county ski trips, Tllberg said, “We went off and poked around frozen bogs. She has a delight in exploring and learning.”

The call for a national park in northern Maine found a sympathetic listener in Roxanne Quimby, who had built Burt’s Bees, originally a Maine company, into a nationally known brand before selling to Clorox in 2007. Quimby used some of the proceeds to buy land south and east of Baxter State Park, intending to give it to the National Park Service.

Ultimately, Quimby assembled more than 87,000 acres by the summer of 2011. Johnson said of Quimby, “She announced she had all this land and wanted to donate it.” At first, things went well, “She represented it as a patriotic thing, that she wanted to give back to the country.”

The idea was not immediately embraced by the Millinocket region. Yet Johnson thought the park plan was viable.

Over several years, they made progress. Opponents reconsidered, especially after the last area paper mill, in East Millinocket, shut down.

One of them was Gail Fanjoy, executive director of Katahdin Works, a statewide organization helping disabled adults live independently, but still headquartered in Millinocket. A self-described “couch potato,” she’s also “a joiner” who led the town council and chamber of commerce, serving in countless volunteer roles.

Gail Fanjoy and Cathy Johnson at the celebration of the establishment of Katahdin Woods & Waters National Monument

Fanjoy, still opposed, attended a meeting where Lucas St. Clair (Roxanne Quimby’s son) and Johnson were speaking. “Lucas sold me, and Cathy hooked me,” she said. “It was all about economic development. I’m the last person you’ll see out in the woods.”

By 2016, when President Barack Obama established the Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument, Johnson had become a hero to many. “She deserved all the applause she received,” said Lisa Pohlmann, “She earned it.”

Despite the triumph, Johnson characteristically thinks more can be done. She’d like to see the Monument expanded to Quimby’s original plan of 150,000 acres and believes it will happen. Beyond that, while Maine has increased protected lands from 5% to 20% of its 12-million-acre forest base, she says, “There’s eight million acres to go.”

As for what techniques – a national park, national forest, state ownership, or private stewardship – would be best, she says simply, “I’m for whatever will work.”

The North Woods program continues. Her successor, Melanie Sturm, is on board, and Johnson said, “I still talk to her as she settles in. I know she’s very eager to get up there. And I love her fire.”

Abridged version of this news story originally appeared in the Spring 2019 Maine Environment newsletter