This is an old familiar tale of wealthy corporations exploiting Maine’s laws and natural resources in pursuit of profit, and the underrepresented people who are being affected banding together and fighting back. The setting for this story is Maine’s State-owned Juniper Ridge Landfill (JRL) in Old Town/Alton; its protagonists are the working-class people living adjacent to the JRL, along with the Penobscot Nation and Maine’s environmental community. The antagonists include the landfill operator, some waste haulers, and one solid waste processing facility in Lewiston.

Maine’s lawmakers will ultimately decide how this story ends. In 1989 the State of Maine passed landmark legislation prohibiting development of new commercial landfills because lawmakers were worried that Maine would become New England’s dumping ground. The reason for this is because transfer of waste between states by commercial entities is protected by the federal interstate commerce clause. The simplest way to prevent waste from coming to Maine was to limit commercial landfills, or to have landfills instead be owned by a non-commercial entity, like the State of Maine.

That’s why, in 2004, the State purchased JRL—to protect this landfill space for the needs of the people of the state of Maine. The State contracted with New England Waste Services of Maine, LLC, a subsidiary of Casella Waste Systems, to operate the landfill for 25 years. They paid the State millions to utilize the landfill, and they are responsible for all the financial obligations of landfill operations. They also profit from bringing waste to the landfill.

Out-of-state Waste, Outsized Influence

JRL is unique in that it is designed to only take “special waste,” which primarily comes in the form of toxic construction and demolition debris and processing residue that contains lead, mercury, and arsenic. It also takes sludge that has been contaminated with cancer-causing forever chemicals known as PFAS. The landfill was not originally intended to take regular household trash, nor waste from out of state. However—because of the outsized influence that companies that profit from importation and disposal of waste have on our laws and regulations—that is exactly what is happening.

JRL is unique in that it is designed to only take “special waste,” which primarily comes in the form of toxic construction and demolition debris and processing residue that contains lead, mercury, and arsenic. It also takes sludge that has been contaminated with cancer-causing forever chemicals known as PFAS. The landfill was not originally intended to take regular household trash, nor waste from out of state. However—because of the outsized influence that companies that profit from importation and disposal of waste have on our laws and regulations—that is exactly what is happening.

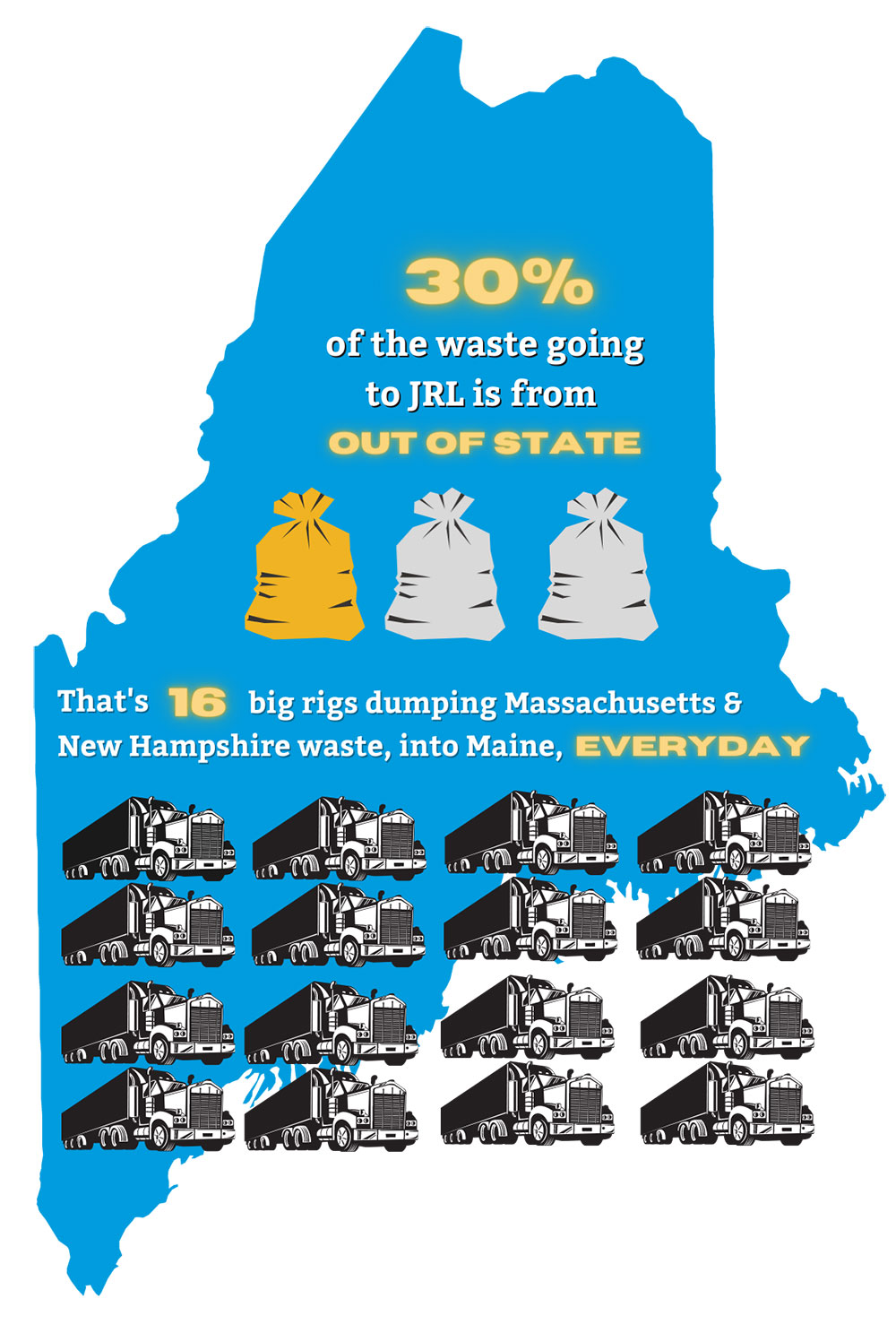

About 30% of the trash going to JRL each year is construction waste from out of state—the equivalent of sixteen forty-ton tractor trailers full of waste every single day of the year. Household waste makes up about 15% of what goes into the landfill. The fill rate at JRL is pacing more than 32% faster than anticipated when the State initially licensed the facility. As a result, the landfill operator has consistently applied for and been granted changes to facility permits and landfill expansions. This has all happened despite legitimate concerns raised by the people most impacted by the existence of this landfill—the ones who live, work, and raise their children nearby.

The location of JRL threatens sites of cultural and spiritual significance to the Penobscot Nation, and the nearby residents are rightfully worried about the safety of the water they drink, the air they breathe, and the fish they catch in the Penobscot River. They also experience the regular occurrence of foul odors, a steady stream of large tractor trailer trucks filled with toxic waste entering their community, and are concerned about the greenhouse gases that escape the landfill’s surface each day. These people have been historically left out of decisions that impact the use of JRL, but now they are organized and fighting back.

Don’t Waste ME

They are known as the Don’t Waste ME group, and they are working alongside NRCM, Community Action Works, and others in Maine’s environmental community to right this massive environmental injustice and prevent Maine from being New England’s dumping ground into the future.

There are three key problems that need legislative solutions:

- Out-of-state waste legally becomes disguised as in-state waste just by virtue of making a pit-stop at one of Maine’s solid waste processing facilities.

- All but one of Maine’s solid waste processing facilities must meet a 50% recycling standard to maintain their permits, except for one facility in Lewiston that happens to receive 90% of its material from out of state and sends nearly all of it to JRL, which gets special treatment by only having to legally meet 20% recycling by 2022.

- Consideration of environmental justice for people impacted by the State’s permitting decisions are not currently required by law.

We have an opportunity to fix each of these problems with LD 1639. If passed, the law would fix all three key problems and significantly reduce the volume of toxic waste that fills JRL each year. And the companies that rely on the status quo will be forced to do the right thing and innovate by finding more sources of in-state waste to support their businesses and find less wasteful ways of operating. Please join us in urging Maine’s lawmakers to support LD 1639.

—by NRCM Sustainable Maine Director Sarah Nichols

Originally printed in the Fall/Winter 2021 edition of Maine Environment newsletter