You’ve seen them. Those video clips of porch pirates helping themselves to packages left on doorsteps. If you’re fortunate, the ones you see include a satisfying gotcha at the end, when the thief gets dusted with spray paint or some other tell-tail punishment for their illegal behavior. Consider adding another element to your viewing: birding! Case in point: A Read More

Nature of Maine Blog

The Natural Resources Council of Maine’s “Nature of Maine” blog gives you the inside scoop on some of the latest issues facing Maine’s environment. From environmental news to threats to opportunities, NRCM is on the frontlines of the latest goings-on—and we’re often leading the charge on efforts to protect Maine’s precious lands, air, waters, and wildlife. Read what NRCM staff members have to say and get the perspective of some of our members and supporters who have been guest contributors.

Perhaps you have an issue you’d like to write about. Maybe you’re an expert on a particular topic and are inspired to share your expertise. Maybe you’ve recently made a visit to a spectacular Maine nature preserve or other natural area and would like to write about it (captioned photos welcome!). For submission guidelines, email nrcm@nrcm.org.

Finch Fever: This Year’s Forecast and a New(ish) Book

While walking our dog through the neighborhood recently, we heard what sounded like the soft, mellow notes of Pine Grosbeaks. We were surprised; it seemed too early for these northern finches to be showing up in Maine. But as we approached the source of the calls, there they were: six beautiful Pine Grosbeaks in the Read More

Musings about Fall Birds in Maine

Fall is, by default, a time of contemplation, as life’s giant cog moves a notch and is expressed in all sorts of ways. Birders like us note that swell of migration from late August to early October, with dribbles of migrants continuing for several more weeks. That’s where we are now, in the birding cycle Read More

Maine Needs Time-of-Use Rates to Drive Down Energy Costs

Climate change is impacting us all. So are rising electricity costs. The high price of fossil fuels and paying to recover from storms worsened by climate change are the top two reasons electricity prices are rising for Maine families and businesses. We know that renewable energy can address both of these problems, by reducing greenhouse Read More

How Mainers are Using Electric Cars and Trucks

Mainers deserve to choose the vehicle that works best for them. For some of us, that’s a truck hauling gear or navigating rough roads in remote areas. For others, it’s a sedan for a daily commute or running errands. For those that can’t afford a car, it may be a bike or a bus. Thousands Read More

Vote NO on Question 1 – Save Maine Absentee Voting

The Natural Resources Council of Maine (NRCM) has joined the coalition of organizations that oppose Question 1 on the November ballot. We would like you to know why we hope you will join us in voting NO on Question 1. A healthy environment relies on a healthy democracy. Much of our work is done in Read More

What You Should Know About Offshore Wind in Maine

Rather than addressing the root causes of high energy costs for Mainers (hint: it’s our over-reliance on fossil fuels), some opponents of clean energy have chosen to spread misinformation. This has led to widespread confusion without offering solutions to the energy affordability issues facing Maine families every day. One favorite target for these false Read More

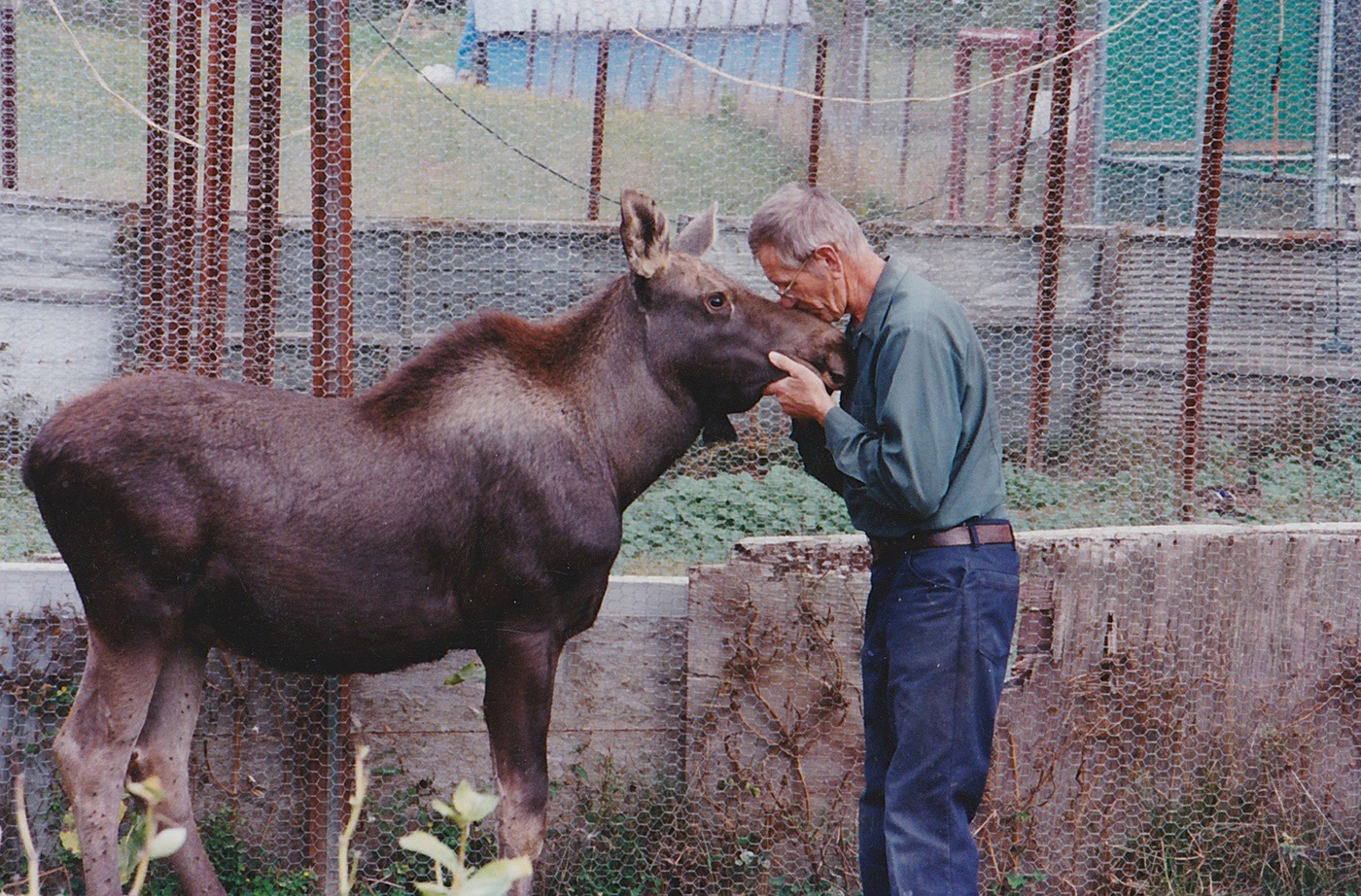

Critter Chatter — The Final Chapter

On September 20, a Celebration of Life for Don and Carleen Cote was held at the VFW in Augusta. As I was driving by the former Duck Pond Wildlife Care Center on my way to this special event, a beautiful male Bald Eagle flew just above my car. A fitting symbol of freedom, strength, and Read More

Caching Up for the Winter

It was one of those crip, golden days that couldn’t decide if it was summer or autumn. The sun lit the treetops along the late-afternoon street. Most leaves were still green, but the maple at the corner was showing off its bright yellows and reds. A tall, brilliant yellow-orange goldenrod at the corner of our Read More