As the campaign to create the Allagash Wilderness Waterway heated up more than 50 years ago, Lew Dietz wrote: “A river that can serve, not the demands of man’s materials needs, but as a sanctuary of the human spirit, is a large river indeed.” Sentiments like this ring true today as our planet is increasingly under strain from human activity, and many of us are seeking out nature as a place of respite.

Maine’s wild places are part of what makes living and visiting here so special. This summer the Natural Resources Council of Maine (NRCM) is celebrating two areas that exemplify the value of wilderness to our wellbeing, to the Maine way of life, and to ecosystem health more broadly.

- July 19, 2020, is the 50th anniversary of the Allagash Wilderness Waterway (AWW) receiving federal designation as a wild and scenic river.

- August 11, 2020, is the 20th anniversary of the state’s Ecological Reserve System.

As we contemplate these remarkable dates, we are also exploring the concept of wilderness and what it means for Maine. Do we have true wilderness remaining in the state? What does wilderness mean to one person visiting from a city versus another who has lived in rural Maine their whole life?

Protecting the nature of Maine by conserving many of Maine’s wildest places has been core to NRCM’s identity since we were founded in 1959 through a grassroots effort to protect the Allagash.

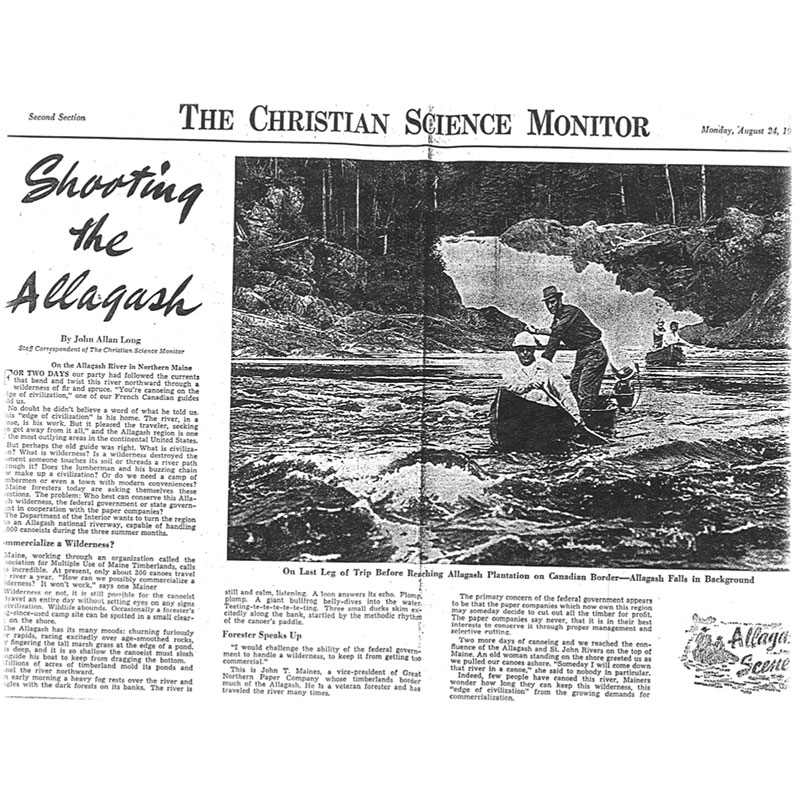

Allagash Falls on the Allagash Wilderness Waterway. Photo by Jay Reighley

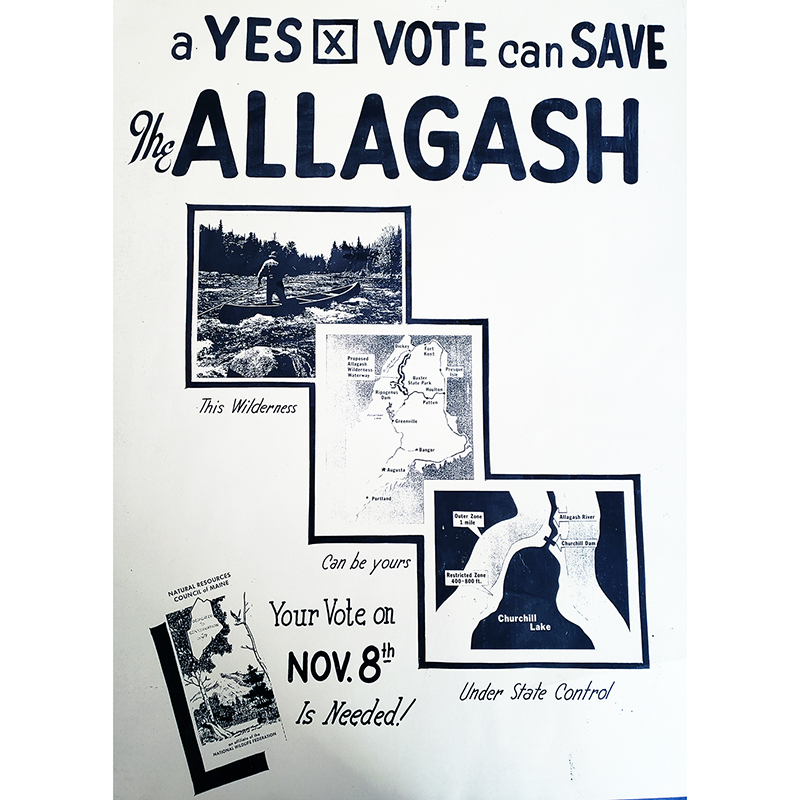

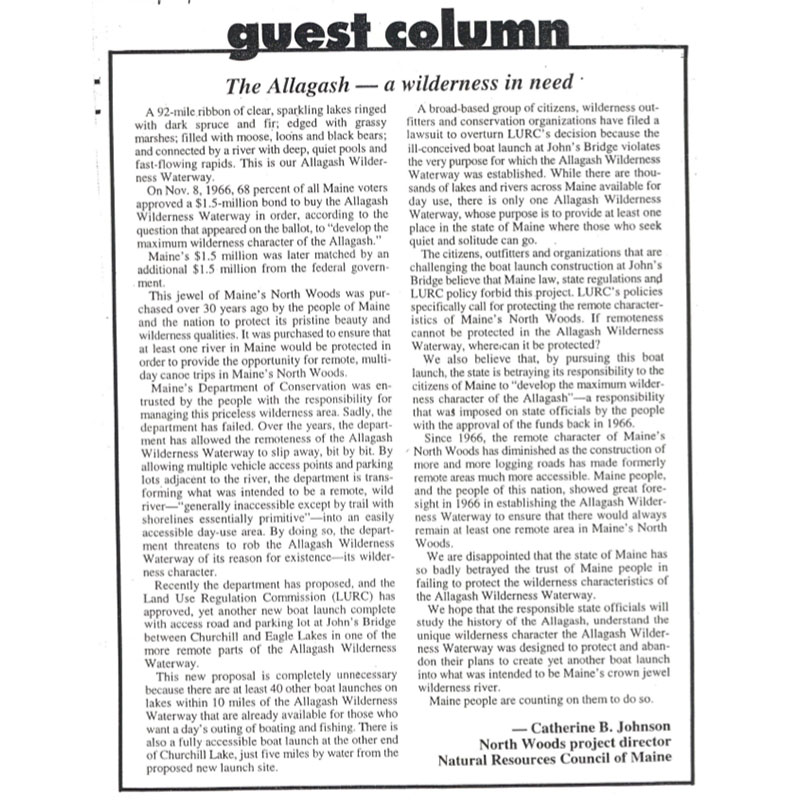

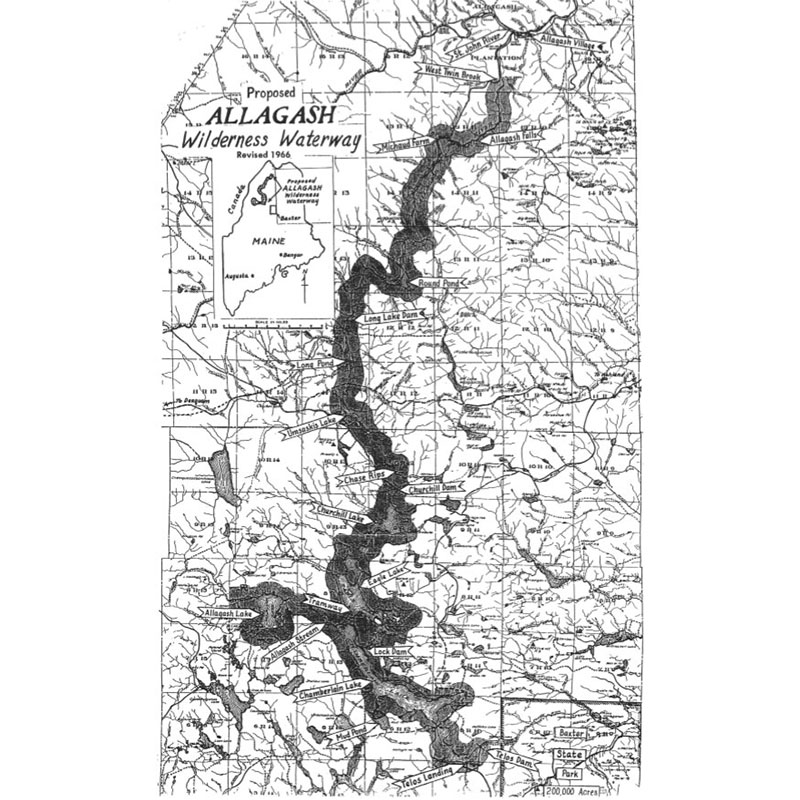

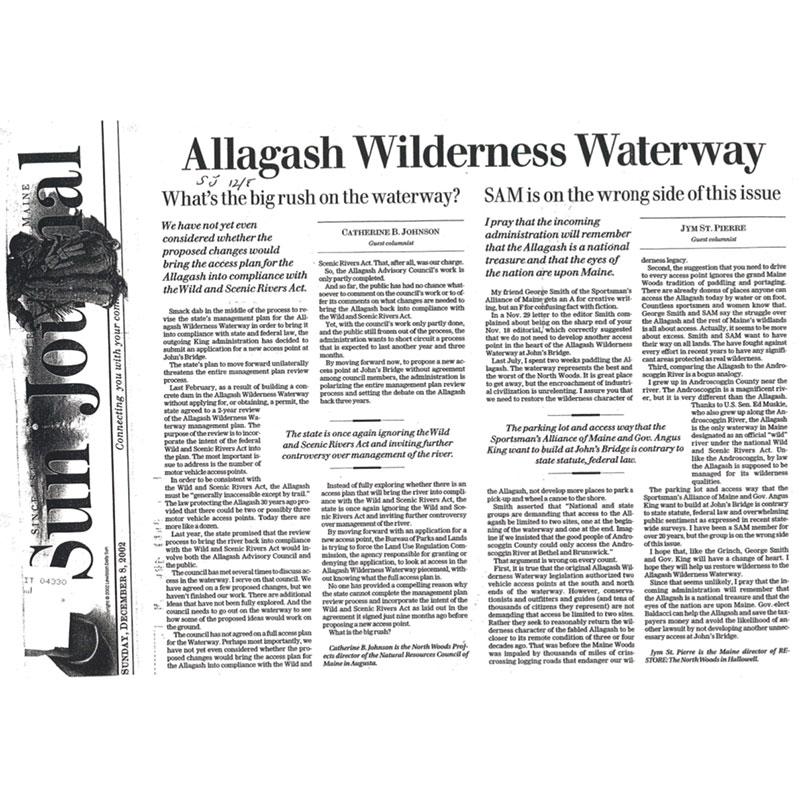

Being a milestone year for the Allagash, we recently looked through our old files to reread the conversations that took place about wilderness in the 1960s around the creation of the Waterway and again in the early 2000s, when there was intense debate about expanded access at John’s Bridge on the AWW. We found some newsletters, newspaper and magazine articles, and letters that show the energy and passion people had for the river way back when and the urgency for protecting it. “Why We Must Save the Allagash” one headline reads, and “Wilderness Under Assault” is the title of another. In yet another article, the author says, “The Allagash needs friends now more than it ever needed them before.”

In 1968, Maine voters passed the referendum to create the AWW by a vote of 68 to 32 percent, and in 1970 the Department of the Interior approved Maine’s request, creating America’s first state-managed/federally protected “wild and scenic river.” Although the AWW is part of roughly 20 percent of Maine’s land that is under some sort of conservation protection, too many precious acres and river miles are still vulnerable to poor management and misplaced development. Anyone who has paddled the Allagash can speak to why it is so important to continue pushing for more wilderness areas across Maine.

Deboullie Ecological Reserve. Photo by David Preston

The Ecological Reserve System, created in 2000 by legislation, aims to protect pockets of Maine’s biodiversity and to allow for long-term research and education so we can better understand how landscapes are changing. This is a particularly useful endeavor with the effects of climate change becoming more evident by the year. Because limited recreation and virtually no timber harvest occur on ecological reserves, Maine’s ecological reserves are like glances into the past.

Please join us in celebrating the anniversaries of the AWW and Ecological Reserve System—some of the last vestiges of wilderness in the state—and all that they provide and represent. Throughout the summer, NRCM is going to release a podcast, post on Instagram and Facebook, and share photos and stories from our supporters. We encourage you to take part in these anniversaries by letting us know what wilderness in Maine means to you, either through a story, poem, photo, or piece of art.

Countless visitors and residents have reaped the benefits of the brazen Mainers who, over many years, stood up for wild places, including the Allagash and ecological reserves. Long before NRCM was established, Henry David Thoreau referred to the “tonic of wildness.” No doubt this was a feeling familiar to our founders.

Today, NRCM continues to carry on the tradition of celebrating and advocating for Maine’s few wild places — the kind of places that feel as though they have never been altered by another human. Not only is this caliber of nature important for public health, but intact, thriving ecosystems are vital havens for wildlife and keep our air and water clean. Though few examples remain in Maine, wilderness needs to continue to be part of a larger conservation and land management effort because of its outsized, enduring importance to ecosystem resilience and human society.

—Melanie Sturm, NRCM Forests & Wildlife Director

Check out some of Maine’s public lands open for hiking, bird watching, paddling, skiing, and more.

Wilderness counteracts degradation

Stay vigilant. Keep up the valuable good work !!!

In the saving of places of natural beauty and wilderness, we are waging a battle for man’s spirit. Sigurd Olson, who helped with the creation of the Allagash Wilderness Waterway while with National Parks and Recreation

I am glad I shall never be young without wild country to be young in. Of what avail are forty freedoms without a blank spot on the map. Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac