People have a tendency, it seems, to want to help birds. We put up feeders filled with seed and suet, telling ourselves that it will do them good while also acknowledging that this will allow us to enjoy hours of watching their behaviors and interactions at close range, without disturbance to them. Some people go so far as to buy special foods like mealworms for them. We make nest boxes and place them around the yard. A growing number of us even improve our yards for them, yanking out invasive and nonnative plants replacing them with native plants that birds love. We keep our cats indoors — and we hope others do, too.

Both the Natural Resources Council of Maine (NRCM) and National Audubon encourage these actions. All are important and helpful, but are they enough to reverse the declines of so many bird populations?

We may be the bearers of bad news, because the answer is, “No, these actions are not enough to make the difference birds need.”

The authors’ yard is a frequent host to Gray Catbirds. The species is a pleasant neighbor but not one of conservation concern. (Courtesy of David Small)

On our own property we know that, in some years, Black-capped Chickadees nest in the nest box we attached to the back of the garage. Most years we have a nesting pair of Song Sparrows in the hedges and an American Robin nest high up in the crab apple tree. Some years, a pair of Gray Catbirds nest in the forsythia. The birds that come to our feeders probably include 40-50 individuals of around 10 species that are regulars. In migration and winter, the number of birds that find food, a sip of water, and some shelter for at least an hour or two is certainly in the many hundreds over the course of a year.

Sure, we can feel good about those numbers as can all of you who can probably make similar or even better claims about the number of birds that you harbor in and near your property.

Like the Gray Catbird, Song Sparrows make great yardmates but do not need special protections. They benefit from actions taken by bird enthusiasts, but what’s really needed for all birds is big-picture conservation action. (Courtesy of Allison Wells)

Still, the reality is that most of the birds that we support in our yards are the common and increasing or stable species, not the ones of conservation concern. The solutions to conserving populations of the majority of birds must be carried out over massive scales in order to be effective.

The waterfowl hunting community recognized this long ago. They advocated for establishment of new U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Refuges and new funding streams beginning with the Duck Stamp program in the 1930s, which has funded the protection of more than six million acres of habitat over the years. Later, in the 1960s, the Land and Water Conservation Fund was established by the federal government to take a small royalty from each sale of an offshore oil and gas lease and apply it to conservation to benefit wildlife, the environment, and all of us. Many millions of acres of wildlife habitat have been protected through this program despite the fact that only a fraction of the money generated from the royalties has ever actually been authorized by Congress to go toward its intended conservation purpose.

Hopefully all of us who care about growing back our bird populations will also think big and expand what we consider part of the “bird conservation” agenda.

That’s why when we talk about legislation that we consider “bird conservation” legislation we talk about the Clean Water Act and the Clean Air Act and, for you policy nerds out there, the National Environmental Policy Act to name a few. Yes, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act is an important part of the solution as well, but these other pieces of legislation impact the future of a greater number of bird populations because they help ensure clean water and air, and smarter, less-harmful development across the entire nation. Those are big-picture, over-arching basic needs, and every creature requires them, whether human or animal, including birds.

We cannot back away from the prospect of tremendous results that come with huge undertakings. The Penobscot River Restoration Project is a great example. Mainers are seeing first-hand the benefits of removal of the Edwards Dam from the Kennebec River in Augusta. Alewives now return by the millions, providing food for increased numbers of Bald Eagles and Osprey, and helping to refuel the cycle of life in the Gulf of Maine. The Penobscot Project didn’t stop at one dam. NRCM and our partners in the project removed two dams and created a realistic fish passage around a third. The river is responding with the same multiplier effect.

Native fish—and birds that eat them, such as Ospreys—have returned to the Penobscot in great numbers since removal of two dams and fish passage at another. The Penobscot Project is an example of large-scale conservation action that’s needed. (Photo by Allison Wells)

Imagine if we could all think that big, or bigger, when it comes to conservation opportunities. What a rebounding effect we would see across broad landscapes and water bodies.

Tying in closely to this, the “bird conservation” agenda must include support for funding for the Environmental Protection Agency, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the National Park Service at the federal level and, here in Maine, for the Departments of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife; Marine Resources; Environmental Protection; Agriculture, Conservation, and Forestry, and the often-overlooked Land Use Planning Commission.

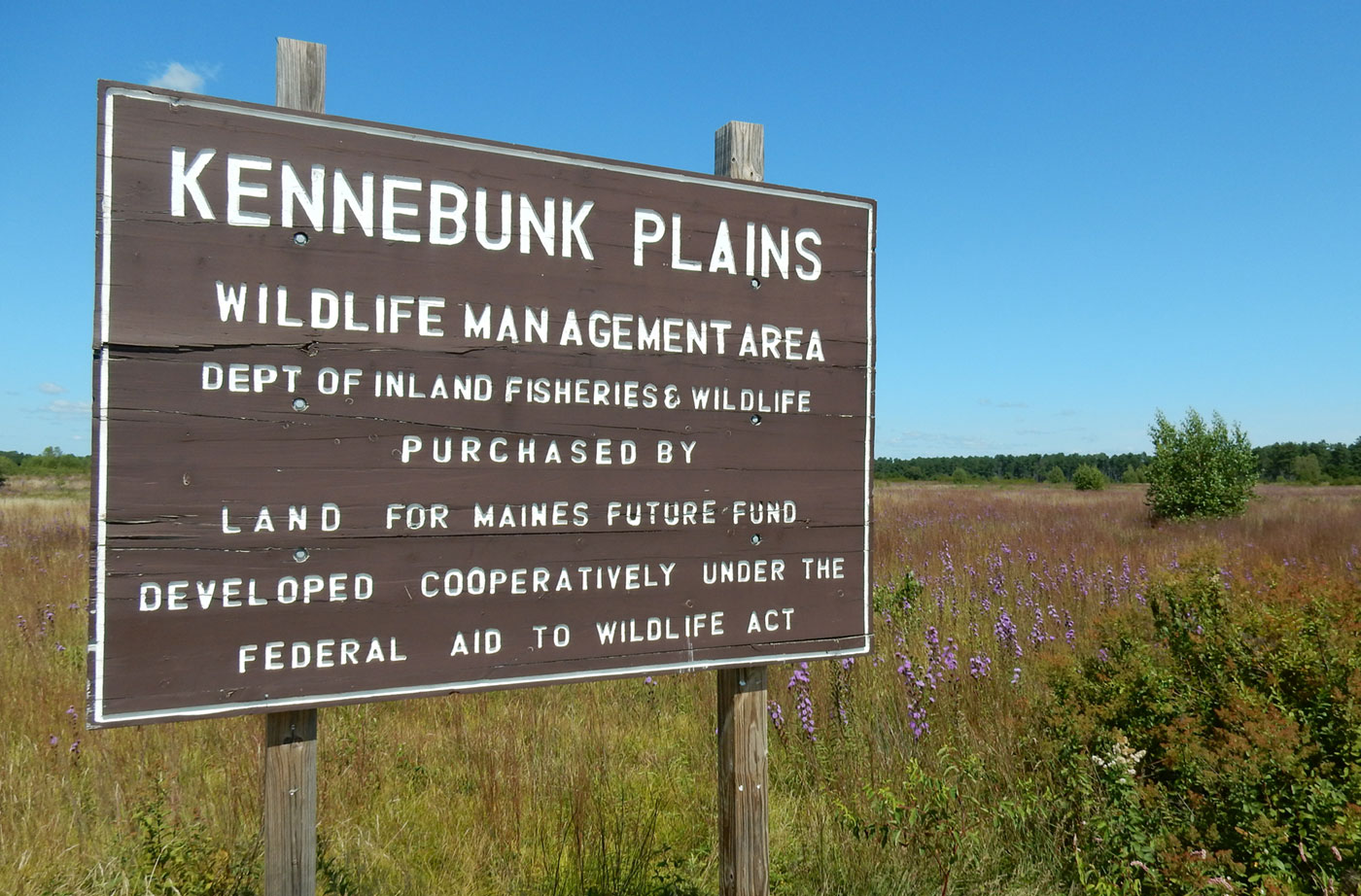

Our “bird conservation” agenda must include renewed support for the bond act to fund the Land for Maine’s Future and for the new recommendations of the Maine Climate Council including the adoption of the new, higher global benchmark for land protection that will provide habitat while also keeping carbon in the ground and out of the atmosphere.

The Kennebunk Plains, projected with help from the Land from Maine’s Future program, is a reminder that birders need to advocate for regular, big-picture funding. (Photo courtesy of Allison Wells)

These are the kinds of solutions we need to adopt if we are to protect and grow the populations of hundreds of millions of birds across hundreds of millions of acres of habitat. We hope that, like us, you will keep taking actions in your backyards to do what you can to help birds. But it is critically important that we all not only support but actively push for the big picture actions that are the only way we will ever ensure that the birds we care about are here for our future and for the generations of our loved ones to come.

Leave a Reply